Artificial Thinking about Thought Experiments

Exploring AI assistance with thought experiments

Interlocutor: Google Gemini 3 Pro

KT: Let’s discuss “thought” experiments. What are they? How do they differ from ordinary experiments?

Gemini: A thought experiment, or Gedankenexperiment, is a hypothetical scenario conducted entirely within the imagination rather than in a physical laboratory. It serves as a mental simulation where you establish specific conditions—often impossible or unethical to replicate in reality—and use logic, established physical laws, or intuition to predict the consequences. These cognitive tools are used across fields like physics and philosophy to test the consistency of a theory, challenge prevailing assumptions, or clarify conceptual confusion.

The primary difference between a thought experiment and an ordinary experiment is the source of the data. Ordinary experiments are empirical; they require physical interaction with the world to gather observational data, which is often subject to measurement error or environmental interference. In contrast, thought experiments rely on a priori reasoning. They do not produce new empirical data but instead reveal the logical conclusions of our existing knowledge or expose paradoxes within our current models. While a physical experiment asks “what happens when we do this,” a thought experiment asks “what must happen if our theories are correct?”

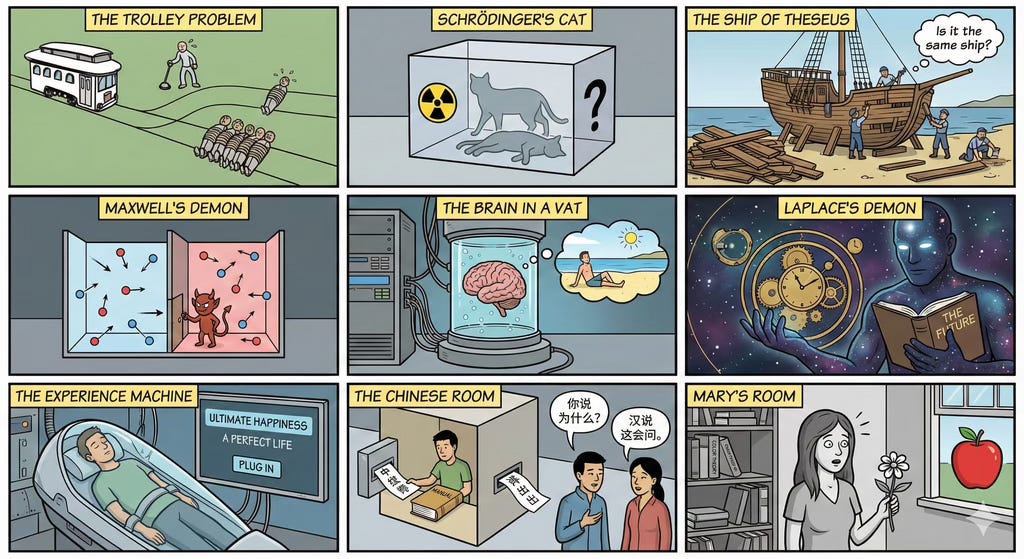

KT: Prepare a 3-by-3 comic-book-style grid in which each cell presents a different thought experiment. Each cell should simply hint at the nature of the experiment.

Gemini:

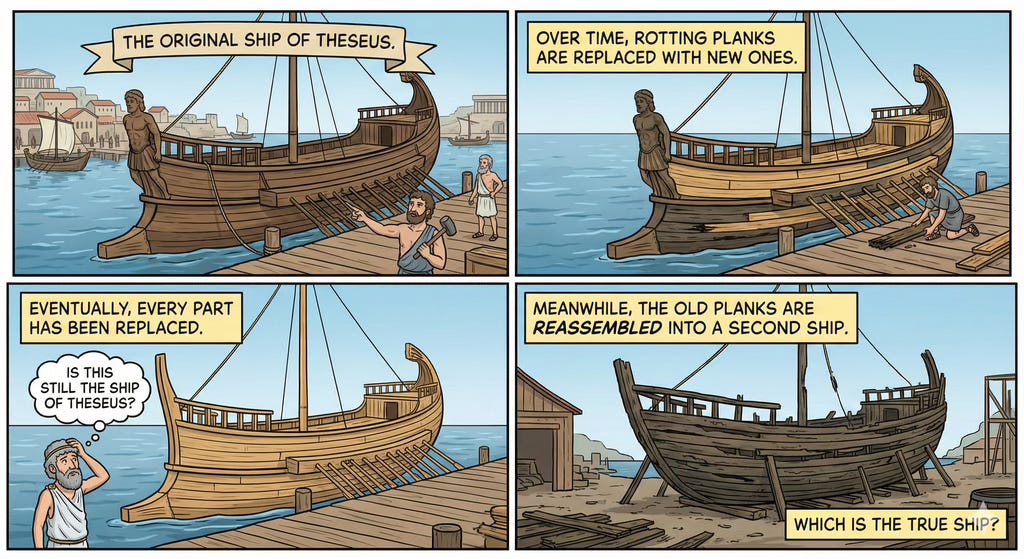

KT: Describe “The Ship of Theseus.”

Gemini: The Ship of Theseus is a classical paradox that explores the metaphysics of identity and persistence over time. First recorded by Plutarch, the scenario imagines the famous wooden ship of the hero Theseus being preserved in a harbor. As the years pass, the individual planks begin to rot, so shipwrights replace them one by one with new timber. Eventually, a point is reached where every single original component has been swapped out, leaving not a splinter of the original wood. The puzzle asks whether this renovated vessel remains the “Ship of Theseus.”

This experiment challenges our intuition regarding what defines an object. Does identity reside in the specific material substance, or is it found in the continuity of form and function? To deepen the paradox, later philosophers like Thomas Hobbes asked what would happen if a scavenger gathered all the discarded, rotting planks and reassembled them into a second ship. We are then left with two claimants: one with the history and continuity, and one with the original matter, forcing us to decide which criterion truly establishes identity.

KT: Prepare a multi-panel illustration that introduces the paradox.

Gemini:

KT: Some thought experiments have connections and similarities to others. What are some such “neighbors” for this one?

Gemini: The Ship of Theseus has several conceptual neighbors that grapple with the persistence of identity amidst change. One direct parallel is Heraclitus’ River, which posits that “no man ever steps in the same river twice,” because both the water flowing through it and the man himself are constantly changing. While the ship focuses on material replacement, the river focuses on the flux of state and the passage of time.

Another close relative is the Grandfather’s Axe, a folk paradox where a person claims to own their grandfather’s original axe, despite having replaced the handle three times and the head twice. This is essentially the Ship of Theseus applied to a simpler object, highlighting how we colloquially assign identity to function rather than matter.

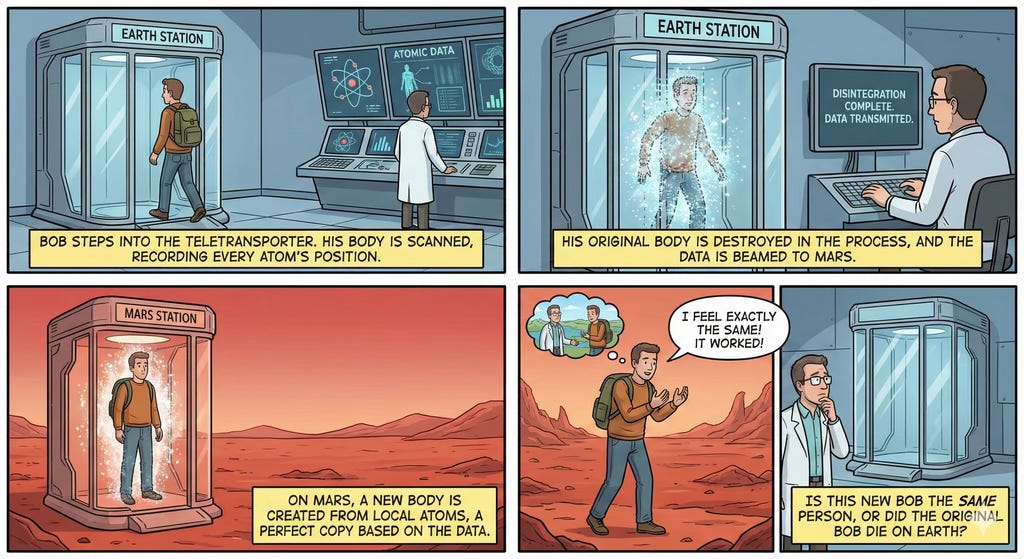

In the realm of personal identity, the Teletransporter Paradox (often associated with Derek Parfit) serves as a modern, high-stakes neighbor. It asks if a person who is disintegrated on Earth and reconstructed atom-for-atom on Mars is the “same” person. Like the reassembled ship, this questions whether psychological continuity (memories, personality) or physical continuity constitutes the “self,” challenging our intuition that we are single, continuous entities.

Would you like to explore the Teletransporter Paradox in more detail?

KT: Yes, present it in a multi-panel illustration.

Gemini:

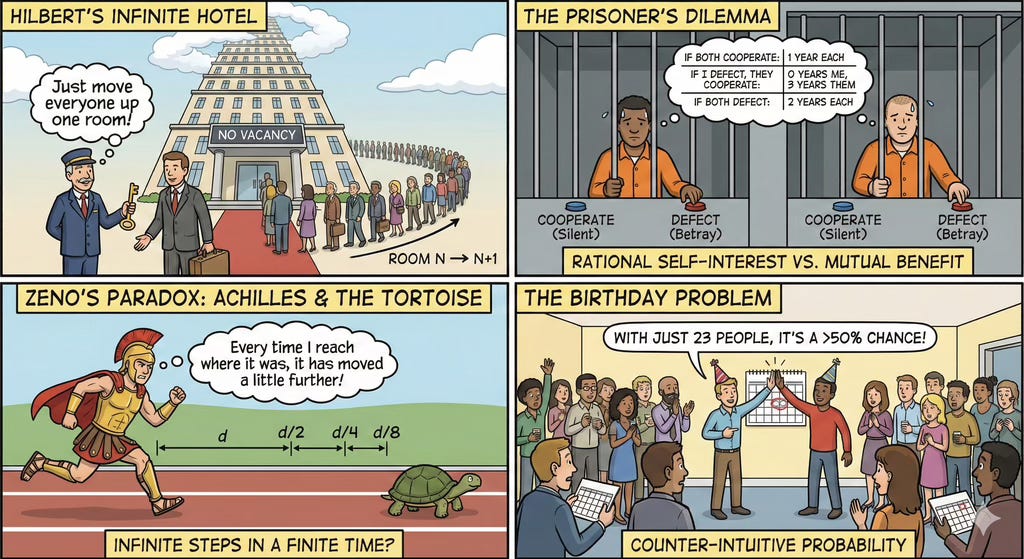

KT: Your earlier selection of thought experiments leaned into physics and philosophy. Prepare a 2-by-2 grid of examples of famous thought experiments from mathematics.

Gemini:

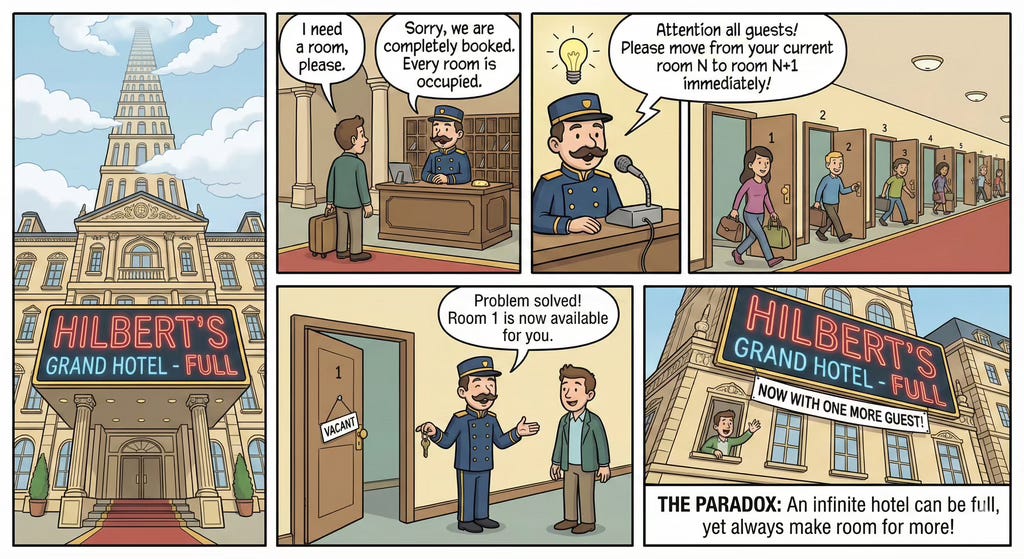

KT: Describe Hilbert’s infinite hotel.

Gemini: Hilbert’s Grand Hotel is a counterintuitive visualization of infinite sets, devised by mathematician David Hilbert. Imagine a hotel with a countably infinite number of rooms (Room 1, Room 2, Room 3, and so on), all of which are currently occupied. In a finite hotel, a “No Vacancy” sign would mean no new guests could be admitted. However, in this infinite scenario, a new guest arrives seeking shelter. The resourceful manager simply asks the guest in Room 1 to move to Room 2, the guest in Room 2 to move to Room 3, and generally, the guest in Room n to move to Room n+1.

This simultaneous shift opens up Room 1 for the new arrival, despite the hotel being “full.” The paradox demonstrates the bizarre nature of infinity: specifically, that a set can be the same size as a proper subset of itself (∞ + 1 = ∞). The scenario can even escalate to accommodate an infinite number of new guests (an “infinite bus”) by asking current residents to move to rooms with double their current number (n → 2n), leaving all the odd-numbered rooms empty for the new arrivals.

KT: Prepare a multi-panel illustration that introduces the hotel.

Gemini:

KT: There seem to be connections between thought experiments and paradoxes.

Gemini: You are right to notice that connection; the relationship between thought experiments and paradoxes is often one of cause and effect, or tool and outcome. A thought experiment is the methodology—the narrative scenario we construct—while the paradox is frequently the result that emerges from it. We use the thought experiment to push a theory to its breaking point, and when that reasoning leads to a contradiction or a counterintuitive conclusion, we call it a paradox. For instance, the “Ship of Theseus” is the scenario (replacing planks), and the resulting confusion about identity is the paradox.

However, not all thought experiments end in paradoxes; some are designed simply to illustrate a principle or establish a new rule. Newton’s “Cannonball” experiment was designed to show how gravity could produce an orbit, resulting in a clear, non-contradictory insight rather than a logical knot. Conversely, paradoxes like “Zeno’s Dichotomy” (where motion is impossible because you must always travel half the remaining distance) use the structure of a thought experiment specifically to expose the limitations of our current understanding of concepts like space, time, or infinity. They are intertwined because the most famous thought experiments are usually the ones that successfully break our intuition.

KT: Let’s consider limits on the generation and “execution” of thought experiments.

Gemini: One of the primary limits on generating thought experiments is the boundary of logical consistency. While we can imagine physical impossibilities (like traveling at the speed of light or a demon sorting molecules), we cannot usefully employ scenarios that are logically contradictory, such as imagining a “square circle.” If the premises of the thought experiment inherently contradict one another, any conclusion drawn from them is meaningless (a principle known as ex falso quodlibet). The scenario must be internally coherent, even if it violates the laws of physics as we currently understand them.

A major limit on their “execution” or utility is the reliability of human intuition. Thought experiments often rely on “pumping” our intuitions to reach a verdict (e.g., “surely you wouldn’t push the fat man onto the tracks”). However, these intuitions are shaped by evolutionary biology, culture, and personal bias, which may have nothing to do with objective truth, especially in realms like quantum mechanics or cosmology where human scale intuition fails. If our gut feeling is the only measuring stick, the thought experiment might just reveal our own psychological prejudices rather than deep truths about reality.

KT: How might we use AI models to design and conduct thought experiments in ways that overcome these limitations?

Gemini: AI models offer a fascinating pathway to transcend the limitations of human-generated thought experiments by functioning as unbiased logical simulators. Unlike humans, whose intuitions are tethered to evolutionary survival and cultural conditioning, an AI can process a scenario based strictly on high-dimensional patterns and formal logic. By feeding an AI a set of premises—even those describing a universe with alternative physical laws—we can ask it to predict outcomes or identify contradictions that our own cognitive biases might obscure. This allows us to “execute” experiments in realms where human intuition fails, such as higher-dimensional geometry or complex quantum states, essentially outsourcing the “simulation” phase of the experiment to a non-biological processor.

Furthermore, AI can help overcome the generation limit by rapidly permuting variables to find novel scenarios that humans haven’t conceived. We can use generative models to create thousands of variations of a classic puzzle, like the Trolley Problem, adjusting variables like age, number, and intent to map the precise boundaries of our ethical frameworks. This turns a single qualitative anecdote into a quantitative landscape of moral reasoning, revealing inconsistencies in our logic that a single isolated thought experiment would miss.

KT: Even taking that for granted, which is quite a leap, how would an AI model recognize a thought experiment has led to a counterintuitive conclusion or an insightful illustration?

Gemini: An AI recognizes a “counterintuitive” conclusion not through emotional surprise, but by measuring statistical divergence—often quantifiable as “surprisal” or high entropy—between a probabilistic expectation and a logical derivation. The model first generates an initial “common sense” prediction based on its vast training data, which acts as a proxy for human intuition. It then executes the specific logical steps of the thought experiment. If the strictly derived conclusion differs significantly in vector space from the initial common-sense prediction, the model flags this mathematical distance as a paradox. It effectively detects a conflict between the general linguistic pattern and the specific logical rule.

Regarding “insight,” the mechanism relies on identifying data compression or topological shifts. If the model observes that a highly complex set of interactions suddenly collapses into a simple, predictive rule, it recognizes this reduction in complexity as a significant pattern. Similarly, by running massive variations, the AI can perform sensitivity analysis to identify “phase transitions”—points where a tiny adjustment to a variable (like the number of people on the track) radically flips the outcome. These mathematical inflection points highlight critical boundaries of a concept, serving as the digital equivalent of a philosophical realization.

KT: This consideration of AI models engaging in thought experiments is a sort of thought experiment itself, isn’t it? On the other hand, prompting you on this topic is just an ordinary experiment.

Gemini: You have encapsulated the recursive nature of our interaction. Imagining an AI that genuinely “experiences” a paradox or possesses an internal state of “surprisal” is indeed a thought experiment, deeply connected to the philosophy of mind. It relies on a priori reasoning about the nature of intelligence and whether syntax (processing symbols) can ever equal semantics (understanding meaning). Conversely, your act of prompting me right now is a classic ordinary experiment. You are manipulating a specific variable—the prompt—and observing the resulting output to gather empirical data on my capabilities.

You are effectively testing the hypothesis “can this language model simulate abstract reasoning?” and measuring the results in the real world. This dynamic places us simultaneously inside a theoretical simulation and a practical laboratory, blurring the lines between abstract philosophy and computer science. We are gathering hard data on how well a machine can mimic the processing of soft concepts.

KT: This dialogue (whatever combination of kinds of inquiry it might be) suggests at least one conclusion: thought experiments rely on the cognitive architectures of the reasoners that run them.